THE WADDEN SEA

As a young university graduate in the sixties of the 20th century I became involved in the environmental movement generated by the publication and discussion of Rachel Carson's 'Silent Spring' (1962) and its dutch follow-up 'Zilveren Sluiers' by C.J. Briejer (1967). My personal wake-up call was the dramatic deterioration of my beloved fresh-water tidal jungle, the 'Biesbosch', in the confluent estuary of the rivers Rhine and Meuse. This was caused by the construction of a dam in the river-mouth (Haringvlietdam, finished in 1969) and an increasing river pollution as a result of massive industrial and communal waste discharges. I participated in protest-marches against the Vietnam war and the use of the toxic pesticide agent orange produced in The Netherlands, and joined the Wadden Society ('Landelijke Vereniging tot Behoud van de Waddenzee') to become a committee member in 1968. This was also the year of the great revolt of the like-minded people of my generation in the western world.

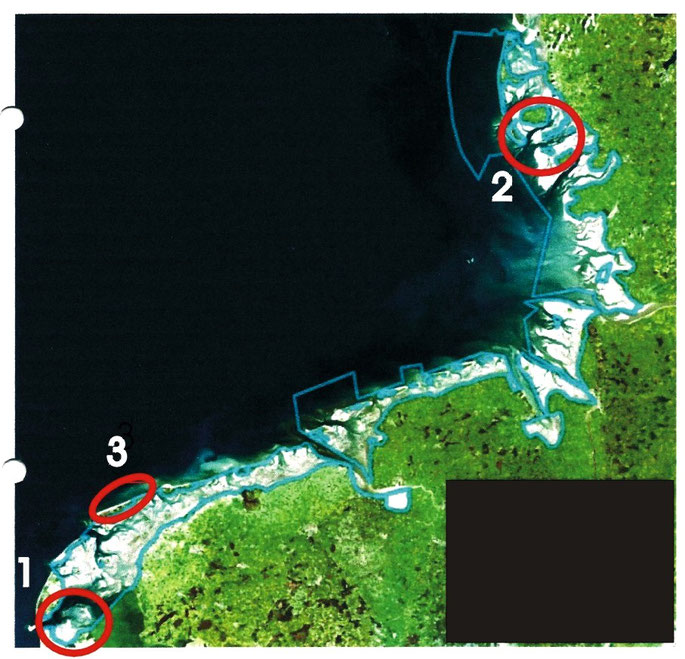

The international Wadden Sea along the northern and western coasts of The Netherlands, Germany and Denmark. Indicated by red circles:

1. the Balgzand area in North-Holland, The Netherlands;

2. the area of the Halligen in Schleswig Holstein, Germany;

3. the island Terschelling in Friesland, The Netherlands.

My first initiative - together with companion Leo den Engelse - was the organization of the resistance to a governmental project aiming at large-scale land reclamation in the Balgzand area, the wild west of the Wadden Sea. The official claim was the realization of harbour, industrial and millitary facilities for the economical development of the naval city Den Helder. Our reaction was the coordination of local environmentalist groups, the collection and publishing of ecological data and the presentation of alternatives. We organized meetings with fishermen and fishery scientists which were on our side and realized a national study conference after the publication of a governmental report on the subject (report of the state commission 'Mazure' and 'Studiedagen Den Helder', 1974). Finally Parliamentary support was begot for a professional economical and ecological cost-benefit analysis of the project and its alternatives, including the zero-option. This was subsequently ordered by the city council of Den Helder and produced by the 'Nederland Economisch Instituut' and the 'Rijksinstituut voor Natuurbeheer' in 1978. The generalized conclusion was that a cost-benefit ratio of about 2,5 could reasonably be expected. That same year the council of Den Helder decided to cancel the whole project.

Newspaper account of our first acte de presence in a public hearing of the municipal council of the former island Wieringen in 1970.

In 1971 I joined the editorial team of the periodical 'Waddenbulltin' and was elected vice-chairman of the executive committee of the society. In these capacities I developed our contact network - in earlier days started up by predecessor Jan Abrahamse - in Germany and Denmark. More specifically, structural support was generated for projects of the 'Deutsch-Niederländischer Verein für Naturschutz im Wattenmeer' in Niedersachsen and the 'Bürger Initiative Nationalpark Wattenmeer' in Schleswig Holstein.

1974, visiting the area of the Halligen in Schleswig Holstein with my partner Tan van Crimpen and Wolfgang Erz, the author of 'Nationalpark Wattenmeer' , experiencing the almost infinite world of the Wadden with Hallig Hooge at the horizon.

In 1973 Jan Veenhuysen, professional editor, photographer and cinematographer, joined the editorial team. He reshaped the Waddenbulletin into an aesthetic as well as a very effective weapon in our nonviolent actions for the preservation of the Wadden. As a handy-sized quarterly journal, combined with a flyer at wall poster format, it proved its qualities conclusively in our support of the farmers of Terschelling aiming at a transition to biological management and the production of their own cheese on the island. A crowd-funding action in 1975 among our members (then ca. 40,000) and the members of Friends of the Earth ('Vereniging Milieudefensie', ca 10,000) resulted in proceeds amounting to the equivalent of € 300,000,-. This was enough to buy and renovate the old dairy factory on the island. A new farmers cooperation was erected and the transition of 12 dairy farms started that same year. The main product, 'Terschellinger Kaas', was succesfully distributed among specialized shops ('natuurwinkels') all over the country and, of course, sold to tourists on the island. Because the use of artificial fertilizers by the farmers was minimized, the traditional ecological quality of the Terschelling pastures was conserved in favor of flowering herbs and characteristic birds like the Grutto and the Ruff c.q. Reeve. In due time, this has proved to be a first class pilot project for other farmers and other islands and, eventually, for the development of a hallmark for sustainable farming as well.

In 1972 the first report to the Club of Rome was published. A year before, copies of the draft of the manuscript were distributed in circles of civilian initiatives, industrial scientists and politicians. In august 1971 I had the opportunity to meet the two main authors, Dennis and Donella Meadows, when they were in The Netherlands for discussion and the collection of comments. The reading of this text and the discussion with its authors had a tremendous effect on me and my companions in various environmentalist committees. We realized as by shock that the exponential growing production and use of fossil energy was in fact the fundamental driving force behind most threats of nature. Our policy regarding the resistance to the exploration and exploitation of gas (and oil) in the Wadden region changed radically from emphasis on the risk of pollution to a plea for drastical reduction against the background of this new vision. This was, however, not taken seriously by the ruling politicians of those days. The development of nuclear energy was, for the same obvious reasons, declined by us as an alternative and consequently we started to support the growing resistance to the construction of new nuclear power plants in the surrounding countries. For a sustainable alternative we turned our attention to Denmark and published papers and reports on the impressive biogas and wind turbine projects there.

What happened to us, happened for the same reasons miraculously to the European Commissioner for Agriculture, Sicco Mansholt, famous for his policy of industrialization of the farmers world. He changed his mind radically almost overnight after reading his copy of the draft and accepted the invitation as a speaker in our annual meeting in Amsterdam on march 1972. He was at that time chairman of the EU Commission and made use of this opportunity to express his new opinion a few months before the official publication of the report by the Club of Rome..

Left: front page of a copy of the draft of the first Report to the Club of Rome as it circulated in 1971.

Top right: Sicco Mansholt speaking at the annual meeting of the Wadden Society in Amsterdam (Krasnapolsky), 4 march 1972.

Down right: speakers at the annual meeting of 1974 (Amsterdam RAI) in discussion with the public, from left to right: J.W,Beek (Unilever), J.Tinbergen (Nobelprize economy), O.V.L.Guermonprez (chairman), N.Tinbergen (Nobelprize ethologie) and S.J.Mansholt (EU Commissioner).

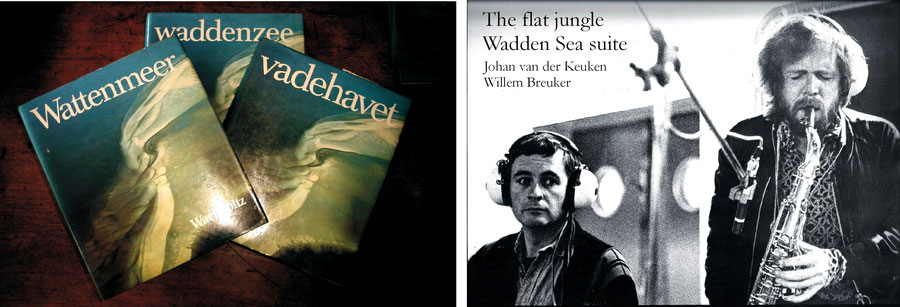

To underline the great value and the problematic nature of the preservation of the international Wadden Sea for the future, we initiated the creation of two modest monuments for a wide public:

- the monograph 'Waddenzee', translated for distribution in Germany and Danmark as 'Wattenmeer'

and 'Vadehavet', with Jan Abrahamse as editor in chief in 1976;

- the film 'De platte jungle', also in english and french versions as 'The flat jungle' and 'La jungle

plate', conceived and produced by Johan van der Keuken with music by Willem Breuker in 1978.

Awareness of the public consciousness, raised after well over ten years of environmental actions, was the basis for a governmental letter of intend published in 1976. It implied the recognition of the whole Wadden Sea area as a managerial unity, and the need for the protection of its ec0logical values by law. We, our legal specialist Karel van der Zwiep and I, collected and structured the opinions of our committee companions and our advisers on this subject. We delivered it as a comment to the Minister of Rural Planning and next, in 1977, the Parliament passed the first 'bill' on this sublect, the 'Planologische Kernbeslissing Waddenzee'. This became the prelude for the first Trilateral Wadden Sea Convention (Wilhelmshaven, 1987) and eventually the recognition by the Unesco as Worldheritage in 2009.

THE RHINE ESTUARY

There were, however, environmental threats far beyond the influence of the rules of national policies. Scientific investigation had proved that almost all the mud sediments in the Wadden Sea originate from the river basin of the Rhine. The mud particles are in turn the carriers of polluting chemicals (e.g. mercury compounds, chlorinated hydrocarbons etc.) in high concentrations. After sedimentation, and gradually deliverance to the aquatic ecosystem, these chemicals implement their effects in the network of food chains with lethal results for animals at the end of it (e.g. the Seals, Terns, Eiders and Salmonid fishes). But their origin was far away and widely distributed in the industrial zones between Basel and Rotterdam.

This was in 1976 the motivation for a cooperation of all national environmental organizations in The Netherlands, crystallized in the 'Comite Rijnappel' of which the coordination was consigned to me. With the intention to find means to activate the public attention in all riverain states, I consulted allied organizations in Switzerland, France and Germany. It was in the air evidently, because in shortest time an international team was formed which gathered a few times in Zürich and decided to organize a travelling demonstration for a fundamental clean-up of the Rhine. A caravan of cyclists, moving in three weeks from the source to the estuary, every day meeting local environmental groups as hosts and everywhere presenting themselves with their message at the gates of governmental authorities and industrial complexes. And in the meantime, of course, drawing the attention of the press. That was the idea, and almost exactly so it was realized.

On july 21, 1977, an international group of about 200 cyclists, aged from 10 (Martie van den Burg, I will never forget her) to 67 years, started the voyage in the first town downstream the sources, Domat-Ems in Switzerland, and arrived in Hoek van Holland at august 11. On the way the caravan increased in numbers to about 300 and delegations were invited by the European Parliament in Strasbourg and the dutch Parliament in The Hague. The attention of the press (newspapers, radio and TV) was unexpectedly high and well informed.

Photo top right: the caravan was welcomed in Rotterdam by the major, Van der Louw (left), at the doorsteps of his city hall. Charles Rossetti from France, our companion from the start who originally launched the idea of a cycling demonstration , explains his motivation for the public armed with supporting banners at the Coolsingel. Below: our modest cycle pennant.

The most impressive confrontations during the tour were those at the construction sites of nuclear plants in France and the BRD. Several of them were occupied by strongly motivated local protest groups which acted as friendly hosts for the passing cyclists. How different was this at the site of one of the largest nuclear projects in Europe, the almost finished 'fast breeder' in Kalkar, Nordrhein-Westphalen. No occupants here, only cows in a pasture dominated by barricades of barbed wire. Our host was farmer Maas, neighbour of the reactor under construction who offered us a barn to spend the night and discuss our strategy. That was to move on in silence the next morning and come back in two months on september 24 to join the demonstration of the civil initiative 'Stop Kalkar' announced for that day. This was to become the summit of the nonviolent actions of the anti-nuclear-power movement. About 50,000 protesters were prevented to enter and occupy the site by a gigantic power of heavily armed military and police officers creating a sinister atmosphere of terror. The demonstration passed off peacefully, however, and became a historical example of civilized resistance.

The construction of the plant, an 8 billion DM project, was finished in 1985 but it was never started up and was eventually cancelled by the BRD federal government in 1991. The complex is now used to accomodate a fun-fair with the name 'Kalkar Wunderland'.

left: the Rhine cyclists discussing their strategy in the barn of farmer Maas, neighbour of the Kalkar nuclear plant under construction..

right: impression of the presence of military and police during the demonstration at september 24, 1977.

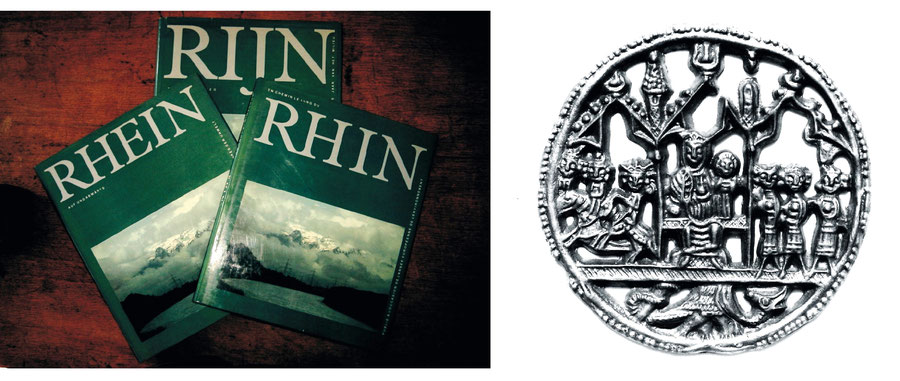

In 1986 I was invited by publisher Uniepers to write an essay on the Rhine intended to become the governmental contribution to the European Year of the Environment 1987. As it happened to be, I recently had revisited the Rhine for a retrospective of the demonstration ten years before. Things had changed, but in which direction, that had been the question for me to answer in a series of interviews on location and broadcasted live by radio. I used this experience to build the essay which was, together with a photo collection, published as a book entitled 'Rijn' which was presented as a herald for the international Rhine Conference to be held in 1988 and distributed among the governmental institutions of all Rhine riverain states.

The paramount positive changes that could be observed at specific locations after ten years were convincing but isolated facts, the raising of the public awareness was less evident. This came to light in a dramatic event, also ten years later. At october 1, 1986, a large depot of the chemical concern Sandoz near Basel got fire and burned down, causing a deadly pollution of the Rhine. I happened to be there because of the radio interview tour and saw how in the next days the buildings of Sandoz were stained all over with paint by furious citizens. Two months later the case was presented at a Rhine Tribunal in Auggen, immediately followed up by the 'Aktion Menschenkette' (aiming at a human chain from Basel to Rotterdam) in which an estimated number of 15,000 persons participated and all Rhine bridges from Basel to the Ruhr were occupied or symbolically blocked by banderoles and tapes........ Things had changed indeed.

left: the Netherlands presentation for the European Year of the Environment 1987.

right: a copy of the mediaeval pilgrims medal of Cologne, offered to the cyclist caravan by the major of the city.

LITERATURE.

Boom, J. et al. (red.) - Waddenbulletin - jaargangen 1986-1979.

Abrahamse, J., Joenje, W. en Leeuwen-Seelt, N. van (red.) – Waddenzee, natuurgebied van

Nederland, Duitsland en Denemarken - uitg. Waddenvereniging en Vereniging tot behoud van

Natuurmonumenten (1976), p. 319-324 en 347-349.

Keuken, J. van der - Flat Jungle - film (1978).

Boom, J. en Reppel, W. en M. – Rijn - uitg. Uniepers, Amsterdam (1987), p.16-33.

Boom, J. in Dirks, R.(ed.) – Le Temps des Assassins - uitg. La Longue Vue, Paris (1987), p. 103-110.

Ruiter, F.G. de – ‘Schoon water moet de zeehond redden’, en ‘De Rijn, treurspel in vele afleveringen’,

in ‘In het Milieu’ - uitg. De Arbeiderspers, Amsterdam (1990), p. 78-89 en 11-35.

Tellegen, E. – Groene Herfst, uitg. Amsterdam University Press (2010), p. 260-262.

Freriks, K. – De kleuren van het Wad, van bedreigde zee tot Werelderfgoed, uitg. Van Gorcum, Assen

(2015), p. 69-107.