Left: aerial photo of Saeftinghe with 1 = location of old sheep house, 2 = location of new sheep house, 3 = Hedwige polder

SUSTAINABLE FARMING IN WATERLAND

In 1978 I decided to change the course of my life and to head for a more practical challenge. As it happened this became the restructuring of a dairy farm based on maximal efficiency of the use of energy and optimal recycling of the natural resources. My compass was the experience with the transition of the farming practice on the island Terschelling and with the message of the report to the Club of Rome. I entered into a partnership with a like-minded farmer in Waterland, the region directly north of Amsterdam, with the intention to participate full-time in the farm and to set up the transition together. We developed a detailed blueprint which was published and distributed to generate useful comments from the farmers world and perhaps financial support from anywhere. But recycling and energy efficiency were no popular items in those days, and we had to start with our own means in a local atmosphere of friendly non-believers who prefered to watch our efforts from a safe distance.

Front page of our blueprint and a schematic presentation of its content with far left the main sources - sun, wind and genes - , far right the main products - cheese, meat and natural flora and fauna - and in between the cyclic processes that had to be fine-tuned.

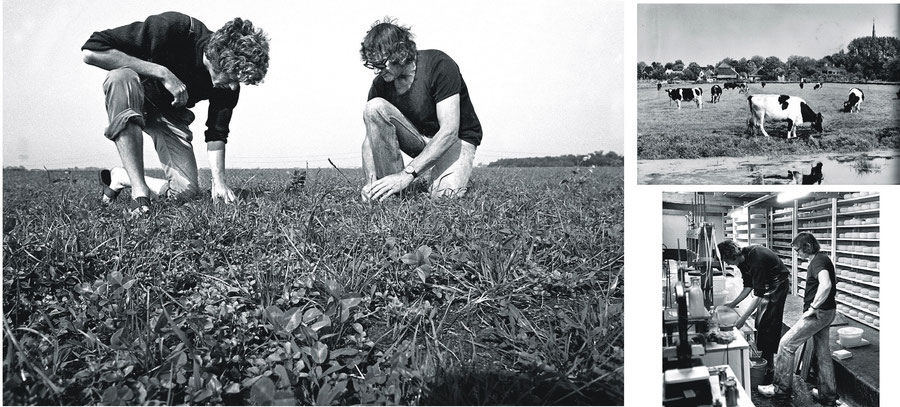

We started the transition with the processing of all our milk to cheese and with extensive tests on optimal pasture management. Here we got, to our great surprise, the active support of quite a lot of consulting and scientific institutions. This input was very stimulating and created a professional atmosphere around our pioneering intention. The farm became a focus of active interest of university students, pupils of agricultural schools and strongly motivated volunteers which gave our project an unexpected and enduring spirit of youthful optimism.

Left: inspection of the pasture on the growth of herbs, particularly the nitrogen-binding clover, after the first year without artificial fertilizer.

Top-right: our cows (ca. 45) of the sound Frisian-Holland breed.

Below: our farm-scale cheese factory

In a few years time the farm, symbolically baptized 'De Domme Dirk' (Ignorant Dick), became an accepted phenomenon in the village and attracted the attention of the press, regional as well as national, because of its unusual appearance as a bee-hive with a coming and going of volunteers, customers for the cheese shop and visitors of our yearly art expositions. We were interviewed regularly and invited to present our project on student meetings and professional congresses. There were, of course, more comparable initiatives, together resulting in an atmosphere of a growing interest in sustainable farming and the need for some form of regulation. So it happened that we got the opportunity to participate in the formulation of the first guideline for the EKO hallmark of 'biological agriculture' which was launched in 1982.

The installation of a large windmill for electricity production had appeared to be not feasible. Consequently, our greatest technical challenge became the development and construction of an installation for the production of biogas and electricity on the scale of our farm. We managed to get support for this idea by specialists of Wageningen University and Research (WUR), the governmental organization TNO (applied scientific research), the engineering company 'Centrum voor Energiebesparing' (CE) and some others. These generated in turn a complete financial support by the Ministry of Housing, Rural Planning and Environment (about the equivalent of € 300,000,-). The coordinated work on the design of a prototype installation for the average dairy farm in Western Europe - about our size and the interest of commercial construction companies - started in 1979 and was completed in 1981. The village council welcomed the project with enthusiasm and granted the building license after a period of public access to the documents ....... but made an almost fatal administrative mistake. The procedure had to be started once again, now resulting in legal objections and pressure on the council members to suspend the licence in this second round, which was granted.

This was, however, not the end of the story. Another farmer in a village nearby was interested and became partner in the project. The installation was erected there, performed very well and could be tested intensively during three years. Then it was already outdated as a prototype because of technical innovations and the rapid rise of the average farm size, but it had played its pioneering role.

Of all our contacts, that with the European Cooperation Longo mai in France was probably the most inspiring. It was started as a small community of university students and artists from Vienna, Paris and Berlin who retired on a deserted property in the french Provence after the uprisings of 1968 in those cities. They had set up an idealistic farmers existence based on the keeping of mountain sheep and the cultivation of vegetables without pesticides and artificial fertilizers. Pivotal in their activities was a professional group of musicians - the Comedia mundi - performing with gypsy melodies and anti-fascist protest songs from pre-war Germany. They made tours all over Western Europe and visited us several times, arranged performances for us and our customers and created an unforgettable atmosphere of festive solidarity.

Left: the design of the biogasplant for 'De Domme Dirk' in Broek in Waterland and its realization in Assendelft in 1982.

Right: performance of the Comedia mundi for our customers in 1980

In 1981 I left De Domme Dirk, and my companion and his volunteers successfully carried on with the project for another ten years. Then he retired and the land was taken over by a neighbouring farmer who recently was switched over to EKO management.

FARMING IN THE TIDAL WASTELAND SAEFTINGHE

In 1981 I got a contract for the nature management of the tidal wasteland Saeftinghe (Verdronken Land van Saeftinghe) on the Dutch west bank of the river Scheldt. It has an area of ca 3000 ha, is the last natural reserve of this type along the continental coast of the North Sea and is characterized by a vegetation of salt-liking plants, many large and small deeply eroded channels and a great potential as a refugium in wintertime for migratory birds. Because of the funnel-like structure of the Western Scheldt the tidal regime here is rather extreme with tidal differences ranging from 5 to more than 9 meter depending on the quarters of the moon and direction and the power of the wind. Traditionally the area was used by shepherds, herding their flocks of sheep between the high tides and creating a mosaic of salty pastures which were in turn used by large foraging groups of different bird species, mainly geese and ducks.

But things had changed rapidly during the last century. The Scheldt and its tributaries became the most polluted river system in Western Europe bringing almost all water life from mud worms to seals to the brink of extinction and intoxicating the plants and threatening the health of the sheep grazing on them. In the same time the hunt on waterfowl was intensified to such a degree that tens of thousands of arctic geese, which used to spend the winter period here, lost their refugium. When the last shepherd retired and sold his flock in 1981, Saeftinghe was degraded, silent in all seasons, in spite of its official status as nature reserve. It was my commission to try to turn the tide.

Right: old sheep house at low tide and at high tide spring

I took over a flock of about 200 sheep and a worn-out sheep house in the township Emmahaven at the southern edge of the tidal pastures and started the project as a new partnership with a young and professional educated farmer, Lukas van Crimpen. Because of the rather primitive circumstances - there were no fences or escape facilities in the whole lease area outside the dikes - I, and my sheepdog Joyce, were for almost five years forced to become shepherds on a daily base like my predecessors had been for centuries. In that same period my companion took care of the building of a new sheep house, financially supported by governmental and private funds, and the supply of hay and straw for the animals in winter times. Together we planned a crossbreeding program in order to create a new type of sheep, the Saeftinger, better adapted to the harsh environment out there.

Left: 12 sheep of the Russian Romanov breed intended for cross-breeding with Brittish Suffolk, held in quarantaine after arriving.

Right: active Suffolk ram in our new open front sheep house.

Impressions of daily circumstances in summer and in winter time.

Regarding the threatening intoxication of the tidal water, the sandbanks and mud plains and the vegetation, by the heavily polluted river Scheldt we acted along two lines.

Firstly, the Netherlands Central Veterinary Institute (CDI) was asked to carry out an investigation on the contamination of the soil, the vegetation and the sheep with toxic heavy metals (cadmium, copper and lead). This resulted in the conclusion that the soil and the water were heavily contaminated indeed, but that the vegetation and the animals grazing on it were charged to a much lesser degree. The direct cause of the disappearence of almost all life in the aquatic ecosystem was clear now, but the keeping of sheep could be carried on relatively safe. The effect on the economical profitability, however, was less optimistic. The conclusions of the investigation were made public, appeared with big headlines in the regional newspapers, and our best direct customers (quality butchers and the catering industry) started asking difficult questions.

Secondly, the International Center of Water Studies (ICWS) erected by Jan Dogterom, my successor in the Wadden Society, asked us to cooperate in a first pilot study on the exact tracing of the sources of river pollution by a newly developed method (Fliessende Welle). The idea was to do this in the compact industrial zone of Antwerp along the banks of the Scheldt. Our local informants could provide for information about the exact location and origin of underwater industrial discharges, and a provisional field laboratory could be installed in our sheep house. Thus it was done.

The pilot was successful, and was immediately followed by a whole series of comparable studies in the industrial zones of the Rhine and its tributaries. Publication of the results, starting in 1986, had an amazing stimulating impact on governmental and industrial initiatives for massive clean-up operations.

Netherlands and Belgian newspaper headings concerning the battle against the pollution of the river Scheldt.

In the first ten years of our project the size of the sheep flock rose steadily from the level of 200 to 600 ewes thanks to the prolific nature of the inbred Romanov's. Simultaneously, in the field, the mosaic of salty pastures extended considerably, followed by a steady rise of the number of overwintering geese and ducks. This was not only a delight for conservationists, but also for a small group of legal hunters who intensified their activities proportionally and even invited a growing number of french colleagues to participate. The result was an almost continuous disturbance and the scaring away of the migratory birds.

Relative to the goal of an optimized ecosystem, this was of course largely counterproductive. Because this appeared not to be the view of the authorities, we started an appeal for support by regional and national conservationist organizations in The Netherlands and Belgium which resulted in an orchestrated press campaign and an official parliamentary interrogation of the minister of agriculture and nature management. Subsequently, the hunting permit was adjourned and eventually, after a couple of years, cancelled definitively. The last hunting party was in 1989, the year of the campaign, and from then on peace was restored in Saeftinghe and the number of migratory guests could rise to a new equilibrium, indicated as numbers of geese, from a few hunreds at the start to between 50,000 and 80,000 ten years later.

Netherlands and Belgian newspaper headings concerning the hunt conflict.

Left: large group of migratory geese arriving in Saeftinghe for survival in winter time.

Middle: graphical presentation of the simultaneous rise of the numbers of grazing sheep (black line) and overwintering geese (red line).

Right: Cranes, incidental visitors on their migratory route between the Baltic coast and Central France.

Between 1990 and 1995, Saeftinghe was visited by a series of extremely high tides, the first on februari 26 1990. With a shock this made me realize our vulnerability relative to the power of nature. Consequently, because evidently the risks were becoming too great, my companion and I decided to prepare for withdrawal , which eventually happened in 1995. I had to leave behind my best friends: my partner Tan who died in 1988, my guides in the regional sheep world, the Flemish shepherds Maurice Cant and Charel Feyen, and my three dogs Joyce, Bor and Snip, which I buried after their death in a rescue mound in the middle of their territory.

Left: newspaper account of the extremely high tide of februari 26, 1990, the first of a threatening series.

Middle: artist impression of Maurice Cant and his dog, saving a wedged sheep from drowning in the rising tide.

Right and below: the only tree in Saeftinghe, marking the grave of my dogs.

LITERATURE

WATERLAND

Edel, B. en Boom, J. – Geintegreerde Landbouw, naar een landbouw die past bij hedendaagse

doelstellingen van maatschappij en milieu - Uitg. Vereniging Milieudefensie, Amsterdam (1980).

Huurdeman, P. – Waterland door de eeuwen heen - uitg. Hoogheemraadschap Waterland (1980), p.

111-119.

Nes, W.J.van en Hoogeveen, H. – Ontwikkeling van een goedkope mestvergistingsinstallatie voor de

middelgrote melkveehouderij - uitg. Centrum voor Energiebesparing, Delft (1985).

Meulen, H. van der en Rodenburg, J. (red.) – Slimme Streken - uitg. Roodbont, Zutphen (1996), p.

20-24.

Kuit, G. en Meulen, H. van der – Rundvlees uit natuurgebieden - uitg. Circle for Rural European

Studies, LU Wageningen (1997), p. 54-63.

Broekhuizen, R. van et al. (red.) – Atlas van het vernieuwend Platteland - uitg. Misset bv, Doetinchem

(1997), p. 36 – 38.

Graf, B. – Longo mai, Revolte und Utopie nach ’68 - uitg. Impr. Vial, Chateau-Arnoux (2008).

Terwan, P. en Stoop, J. – Boeren in Waterland - uitg. Stichting Matrijs, Utrecht (2017), p. 34-36 en

111-114.

SAEFTINGHE

Boom, J. – Over schapen en boeren langs de kust - uitg. Waddenvereniging, Harlingen (1980).

Saman, E. - 'Achter onze dijken' - film met opnames start schapenhouderij Saeftinghe (1981).

Boom, J. – Een schapenjaar buitendijks - uitg. Cooperatieve Schapenhouderij

Saeftinghe, Emmahaven (1982)

Leeuwen, N. van en Wolff, W. en I. – Achter dijken en dammen, Zeeland en de Deltawerken - uitg.

Meulenhof Informatief bv, Amsterdam (1983), p. 130 – 135.

Lenjou, W. - 'Schaapjes op het droge' - film over pionierstijd (1983).

Blom, A. - Fliessende Welle Schelde - uitg. International Centre of Water Studies (1986).

NPO-TV - Van Gewest tot Gewest - film. opgenomen in 1982 en 1986, uitgezonden 20-08-1986.

Lenjou, W. - 'Eenzaam samen' - film over Maurice Cant (1987)

Baars, A.J. et al. – Milieuverontreiniging en schapen in het Land van Saeftinge - Landbouwkundig

Tijdschrift juni/juli 1987.p. 28-32.

Baars, A.J. et al. – Fluoride Pollution in a Salt Marsh: Movement between Soil, Vegetation and Sheep

- Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 39, 945-952 (1987).

Baars, A.J. et al. – Environmental contamination by heavy metals and fluoride in the Saeftinge salt

marsh (The Netherlands) and its effect ons heep - The Veterinary Quarterly 10, 90-98 (1988).

Ruiter, F.G. de – Natuurzuivere herstelbeweging, in ‘In het Milieu’, uitg. De Arbeiderspers, Amsterdam

(1990), p. 223-232.

Boom, J. – Weiden in de zee, Zeeuws Landschap 9 (2), 10-12 (1993).

Buth, G-J. – Jan Boom: een ontdekkingsreis tussen maatschappij en natuur, Zeeuws Landschap 9

(2), 13-14 (1993).

Buise, M. en Sponselee, G. – Saeftinghe, verdronken land, uitg. Duerinck bv, Kloosterzande (1996),

p.....

Castelijns, H. en Jacobusse, Ch. – Spectaculaire toename van Grauwe Ganzen in Saeftinghe - De

Levende Natuur, 11(1), 45-48 (2010).

Schipper, P. de – De Sterke van Saeftinghe - uitg. Atlas, Amsterdam (2010), p. 208-222.

Buise, M. – Schapers en Schapen, Schorren en Polders - uitg. Oudheidkundige Kring ‘De Vier

Ambachten’, Jaarboek 2012-2013, p. 102-126.

Deweerdt, H. en De Pue, P-J. – Westerschelde, Droom van een Stroom - uitg. vzw Droom van een

Stroom, Gent (2001).